On the Road Again Consumptives Traveling West

Before antibiotics, tuberculosis was a leading cause of death, a national fixation, and the scourge of artists

Henry Baldwin spent the month of May 1849 keeping vigil at his young married woman'due south bedside in Newport, New Hampshire. "Here I sit down in the dear chamber—the 'conjugal chamber'—where ane short year ago I first pressed to my heart a young and pure and blooming married woman," the engraver and illustrator wrote in his diary. "Then how fair and hopeful and cute she seemed, with the bloom upon her cheek . . . Now, alas, she lies all pale, stricken, and dying." Marcia Baldwin, 21, had consumption, an inscrutable wasting affliction that terrified and obsessed Americans.

Antibiotics' arrival in the mid-20th century defanged consumption, as tuberculosis was once known, but before the disease—responsible for as many as a tertiary of deaths in America—brought terror. The ailment was particularly feared in New England, where settlement and living patterns—the close quarters of farmhouses and small, tightly knit villages—encouraged its spread. When Rhode Islander Samuel Tillinghast tracked mortality amid acquaintances in the 1750s and 1760s, he plant that over half had fallen to consumption. Transforming life, altering ambitions, and reshaping the very culture, consumption morbidly fascinated Americans.

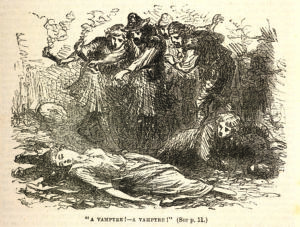

Marcia Baldwin's husband recorded the young woman's eight-month ordeal. "I accept watched her gradual decay," he wrote. "I have seen the full, round, and rosy cheeks fade away, the rubberband steps abound weak and birthday fail, the ringing, pleasant tones of her gentle voice subside to the feeble & broken whisper." In March 1849, Marcia, undone by "a distressing attack of bleeding at the lungs," took to her bed—for skillful. Henry bathed her through enervating fevers, held her as convulsions and crippling pain wracked her emaciated frame, and tried to position her and so she could breathe. "What a dreadful scourge is consumption. It seizes upon the loveliest of world's flowers and blights and withers them abroad," he wrote in early on June. "It loves the carmine cheek, and vampire-like delights to feed upon the ruby-red lips. Ghostliness and pallor solitary remain to mark its desolation wheresover it passes." An entry made weeks later on reads, "The scene is closed. My beloved Marcia has gone and left me here lonely!" But non for long; in 1855 Henry, 39, followed Marcia to the grave.

Marcia and Henry Baldwin both died of pulmonary tuberculosis [Come across "Talking TB, beneath], aka "the White Plague." No i knew its cause or its cure, but anybody knew its symptoms. Commencement, a cough, persisting, perchance unremarked upon, for weeks or months. Next, an intermittent—or "hectic"—fever that weakened its host. Patients lost vigor, grew pale and paler, bodies always more frail. The White Plague seemed to assimilate flesh, every bit if consuming the life force. Animate became labored, and pain tortured the chest and sides. As lesions in the lungs putrefied that tissue, coughing brought upward blood. Morning chills alternated with evening fevers that soaked the body in sweat. At the end, many patients seemed mere skeletons sheathed in papery skin, beset by coughing spasms, unable to depict breath, drowning in bloody phlegm—a horrifying, mesmerizing display of mortality.

The ancient Greeks called tuberculosis Φθίσις or phthisis, meaning "wasting." In early America, doctors trained in the tradition of the ancient Roman physician Galen employed that term, only lay folk said "consumption." Tuberculosis has long been present in North America; traces announced in the basic of pre-contact indigenes. English settlers recognized the disease John Bunyan termed "the helm of all those men of death." Smallpox, plague, and cholera were known to be contagious, but English language and American doctors did not believe consumption catching.

In truth, no one knew how the affliction spread—but anybody knew a consumptive or feared becoming one. Apprehension begat obsession. By the early 1800s, consumption—with its inscrutable and unpredictable course—was haunting American life. Some patients died chop-chop, of "galloping consumption." Others suffered a prolonged "lingering death." A few survived in relatively good admitting delicate health, or even saw their symptoms resolve. Uncertain prognosis fostered both terrible fearfulness that each cough was a death penalty, and fervent promise that it was not.

Cruelly, near consumptives were in the flower of youth. The disease could claim a generation of a family, taking child upon child until the nest was empty. In her diary, Caroline Seabury dolefully recorded the deaths in the 1850s of vii of her 8 siblings on Cape Cod from the affliction. In 1816, betwixt losing two sisters, Phebe Melven, 14, of Concur, Massachusetts, stitched a family history on a sampler.

Her closing poesy reads Unhappy he who latest feels the blow/Whose eyes have wept o'er every friend laid low/Drae'd lingering on from partial expiry to death/'Till dying all he tin can resign is jiff. The Concord Yeoman'due south Gazette noted in 1826, "Though father and mother live to advanced historic period, their children and one thousand-children fall before them by a affliction which no human skill has yet been found able to cure."

Puritan New Englanders stoically accustomed youngsters' deaths as a heart-wrenching manifestation of God's will.

Of his dead offspring, poet Edward Taylor wrote, "I say, accept, Lord, they're thine./I piecemeale laissez passer to Glory bright in them./I joy, may I sweet Flowers for Glory brood,/Whether though getst them greenish, or lets them seed." When all but 3 of preacher Cotton Mather's 15 children died young, Mather kept his grief to his diary; neighbors praised his family for beingness "in total possession of themselves, in patience and benevolence," resigned to God'southward will.

But attitudes began to shift. By the 1790s, Americans were get-go to cover the Enlightenment values placed on reason, science, and engineering. Confidence emerged in individuals' capacity to shape their destiny. Onetime tropes of fate and religion faded; unpredictable and uncontrollable death now unnerved people. Doctors decried "the alarming increase in Consumption in the United States," and warned that the rising generation's "doomed hopes" threatened the nation's futurity. Though consumption incidence had not risen, concern about consumption had, generating an intense focus on its imagined causes and inescapable effects.

Unaware of germs, patients and doctors suspected heredity, environs, and behavior to be at play. Consumptive elites were thought to pass along a predisposition to the malady; a sensitive temperament and a frail frame, it was said, foretold wasting decease. Then, information technology was theorized, did genius, for what burned brightest burned fastest—creative brilliance literally consuming possessors. The middle classes risked consumption in their behavior, said doctors, urging immature men not to frazzle their souls with excessive written report or desk work and cautioning young women against immodest fashions, rib-crushing corsets, and the excessive pleasures of dancing and reading novels. Consumption amidst the poor was often attributed to immorality: promiscuity, insobriety, filthy habits. Environs in the form of arctic night drafts and miasmas—noxious vapors gusting from swamps and boarding houses akin—could roughshod anyone anytime.

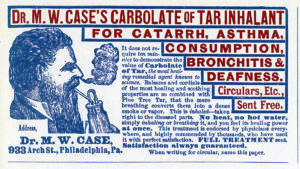

One time consumption "settled" in a patient, the focus shifted from prevention to remedy. Consumptives consulted lay healers, or physicians, or both, and both sectors competed with a gabble of self-described experts, patent medicine floggers, and purveyors of commercial treatments, all promising cures and all driven by the profit motive.

Care took place mainly in the home, and was provided mainly past women. Caregivers relied on accumulated generations of lore. They brewed broths, distilled elixirs, molded lozenges, boiled steamy fumigants, and mixed plasters to save coughing, fever, and pain. Alcohol was a mainstay. Many domestic remedies relied on the magical belief that "like treats like." Blood being idea the font of vigor and spirit, remedies often ran red or invoked it—broth from the meat of a red rooster, milk from a cherry cow. A vogue developed for concoctions made from the spotted oval leaves of lungwort, a plant believed to resemble a set of diseased lungs.

In rural Hallowell, Maine, domestic healer and midwife Martha Ballard made for consumptive niece Parthenia Pitts "a Syrup of Comfrey, Plantain, Agrimony & Soloman's Seal leaves." Parthenia continued to reject. She followed her aunt's counsel and "rose about an 60 minutes past Sun in ye morning time, went out & milkt ye last milk from ye Cow into her oral cavity & Swallowd information technology." Some patients slept in barns crowded with livestock so as to inhale cows' reputedly healthful exhalations; others inhaled fumes from white pitch and beeswax heated over flames. Concoctions fabricated from snails and their slime were popular for soothing coughs and easing animate.

The better off patient might consult a physician trained in bodily humors, an aboriginal Greek theory that in its effort to residual the 4 humors—blood, black bile, xanthous bile, and phlegm—embraced "heroic" therapeutics: haemorrhage and deliberately induced vomiting, diarrhea, and sweating. One handling—based on Enlightenment faith in chemical cures—dosed patients with mercury. Amongst medical practitioners, realists admitted privately that the only treatment for consumption was "opium and lies."

The market flung upwardly an boggling range of regimens and products. Homeopaths believed in plants' medicinal and spiritual powers, and some packaged botanical kits and published books. William Buchan's Domestic Medicine and John C. Gunn's Domestic Medicine, or Poor Man's Friend described treatments in lay language and often represented isolated rural or frontier settlers' only medical resource. Entrepreneurs hawked disease-specific chairs, stoves, and often elaborate animate apparatuses such equally that "great preventative of consumption, and unfailing cure for pulmonary illness…the medicated fur chest protector."

Sales of "patent" medicines exploded. A February 1825 ad for Dr. Relfe's Asmatic Pills informed Columbian Centinel readers that "a lady of Hampden, Me., …seriously afflicted with consumption…and expected to die within a few hours," instead had been restored to health by a single box of that nostrum. Preparations and pamphlets invoked links to Indian methods. The Indian Vegetable Family Instructer promised that its "selected Indian prescriptions" would cure consumption "afterward every other remedy had failed." In the 1840s, Blood brother Corbett'due south Wild Ruddy Pectoral Syrup began a long reign every bit a preferred treatment.

Purified botanicals marketed by the Shakers, a Protestant sect, were thought efficacious confronting consumption ("Complicated Gifts," Feb 2019). Some customers trusted Shakers fifty-fifty more deeply.

The Bradleys of Concord, New Hampshire, a self-described "sick family" with both generations consumptive, sent youngest daughter Cynthia to live at nearby Canterbury Shaker Village in hopes of saving her. Her brother, Cyrus, visited Cynthia in 1833. He was impressed by the Shaker physician and his botanical garden. Cynthia, it seems, was impressed with the Shakers. Cyrus noted: "She has gained much in her health, but zero can induce her to exit the people who have treated her so well." Cynthia never returned to her family, only she survived them all.

Another treatment was to hit the road. Theorizing that fresh air worked wonders, doctors brash patients to journey on horseback or by body of water. Fearing the supposedly noxious effects of damp northern air, consumptives able to afford southern sojourns sought balmier locales. In 1784, minister Elisha Parmele, 29, asked his Lee, Massachusetts, congregation'south leave to travel again to Virginia; ii earlier stays had rejuvenated the ailing preacher simply only temporarily. Congregants assented. Parmele trundled south with his wife in a railroad vehicle trailed past their cow. He died en route. Touring the Caribbean to document life among formerly enslaved people, consumptive abolitionists simultaneously escaped the northern wintertime. The White Plague became conjoined with the struggle confronting bondage. Southerners insisted the flood of consumptives to their region proved its manner of life healthier, but visiting patients, seeing slavery showtime-mitt, often returned foes of the peculiar establishment.

The travel cure spurred demand for accommodations, encouraging construction of health resorts and spas. Turnpikes, canals, and railroads brought patients to facilities at the seashore, in the mountains, and near mineral springs. I man, revisiting a New Hampshire hamlet once known only for commercial fishing, noted that consumptives had replaced cod every bit a business proposition. The seaside village at present counted three hotels—"large, furnished, and supplied with convenience for the adaptation of the sick," plus private bathing and showering facilities and other "inducements to the invalid." Mountain resorts sprang upwards from the Adirondacks to the Appalachians. Spas featuring cold or hot mineral waters, such as White Sulphur Springs in what was and then western Virginia, became particularly popular. Spa proprietors ofttimes enclosed springs in elaborate pavilions, staging concerts and social programs designed to lure the business of upper class invalids.

Some healers created and thrived on cults of personality. In a volume touting his methods, New York City-based Dr. Samuel Fitch claimed to have achieved "a complete cure" for patients through a regimen of "medical inhalation," medicines, and "instruments." Rivals derided Fitch's book as a "quack advertisement" and a "slap-up farce and a complete humbug," but patient Harriet Tappan of Panton, Vermont, was among many who came to his clinic. Following iii months under Fitch'southward care, Tappan lived long enough to marry but within a yr of handling had died.

Jacksonville, Florida, emerged as a winter oasis for phthisis patients. Among treatments available there an observer listed, "the milk cure, the beef-blood cure, the grape cure, the raw-beef cure, the whisky cure, the health-lift cure, the cure past change of climate, and many more…"

Consumption's highly variable course and the survival of but a fraction of patients lent many specious treatments a whiff of validity. Hoping for a miracle, patients mixed medicines and treatments. Julia Pierce of Winsor, Massachusetts, wrote to her sisters in the early 1840s of their younger brother's efforts to regain his wellness. Addison Pierce tried roots, horseback riding, cold water showers, homeopathy, an Indian medico's advice, "taking the waters," sea voyages, and care from a doctor promising a cure or no charge, his sister said. "If it appeared to accept any efficacy, they were willing to give it a try," historian Sheila Rothman wrote.

Desperation powered participants in a bizarre handling pursued by some families who had lost multiple children. In 1788 Congregational minister Justus Frontwards of Belchertown, Massachusetts, having buried iii children, had two more grow dangerously sick.

Neighbors claimed vampirism lay at the root of consumption. They recommended "therapeutic exhumation." Among the recently deceased, these savants proposed, someone was "undead" and rising supernaturally at night to siphon away living siblings' claret. To neutralize this killer, the Forwards had to disinter their expressionless children, identify the vampire, and fire its center or besprinkle its bones. At first horrified, the Forrard in fourth dimension consented. In his enquiry into the ghoulish phenomenon, folklorist Michael Bell has documented instances of lxxx-plus therapeutic exhumations undertaken to cure consumption in New England betwixt independence and the Civil War. The practice survived until the tardily 1800s, its persistence testament to the agony of families stalked past consumption.

With its cause a mystery, its cure unknown, and its prognosis unpredictable, consumption permeated everyday life in the America of the 19th century. Youths suspected of predisposition to the ailment were brash to quit schoolhouse, change jobs, and postpone union or hurry into marriage. Families relocated to supposedly healthier climes. Grown offspring were pressed to return to the homestead to nurse kin or keep a farm running. Bereaved parents lived with punishing loss; dying parents gave their children away to family unit or friends. At society's margins, consumptives faced death on the street or in the almshouse, every bit did their families.

Consumption troubled many leading cultural lights: authors Washington Irving, Nathaniel Hawthorne; and Edgar Allen Poe; philosopher-writers Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau; poet William Cullen Bryant, artist Thomas Cole, and musician Stephen Foster. Death and invalidism drove a melancholy undercurrent in art and literature. Images of mourning maidens aptitude over funeral urns framed by weeping willow branches were allegorical of the era. Printers did brisk business selling mass-produced "memorial prints," lithographs of generic onlookers mourning at graveside, the stone marker's front end left blank for personalization.

"Alleviation literature" emerged—prose and verse saturated in sentiment and crooning of early on partings and doomed amore—romantic, filial, or platonic—as in the 1832 Philadelphia Flake Book & Gallery of Comicalities poem, "To a Friend Lingering With the Consumption": Consumption's lean and greedy worm/Is feasting on thy frame;/And soon, oh! Presently thy worried term/Shall stop, and quench life's flame.

The 1836 Mourner'due south Volume compiled verses along the lines of "And so wasting pain and slow disease traced furrow on the forehead, The grasshopper, alighting, is felt a burthen now. . ." Teacher and poet Lydia Sigourney, a master of this genre whose own consumptive son had died at 19, often was hired to memorialize a schoolmate or child.

Morbid poetasting became a thing. Schoolchildren exchanged "friendship albums" into which they copied morose verse on themes similar forget-me-nots, broken bonds, and imminent partings. Sabbath School Society booklets told of faithful children patiently indelible as death neared, such equally 9-year-onetime Ann Elizabeth Pierce of Massachusetts telling her parents in 1833, I have sometimes wished I was well, but I do not now; I had rather die and be with my savior.

The deaths of consumptive innocents became plot points in potboilers. Fiddling Eva in Uncle Tom'south Cabin past Harriet Beecher Stowe is maybe the best known sick little saint, just consumptive lit had a seamier side. The widely circulated mag Godey'south Lady's Volume featured stories populated by characters undone by vanity, pride, ambition, or animalism. Consumptive heroines and their seductions made the pop-gothic novel a mainstay.

From Clarissa and Charlotte Temple to Les Miserables' Fantine, the Lady of the Camellias, and La Boheme, fallen women rode unbridled passions to consumptive ends, tragically beautiful to the last.

Graveyard humor arose. The Monthly Traveler, in December 1830, noted that "a gentleman met another in the street, who was ill of a consumption, and accosted him thus: 'Ah, my friend, yous walk deadening.' 'Yes,' replied the man, simply I am going fast.'" New York journal Minerva offered verses "On a Admirer Who Married a Consumptive Lady" in August 1823: With a warm skeleton so most,/And wedded to thy arms for life/When death arrives, it will appear/Less dreadful—'tis so like thy married woman.

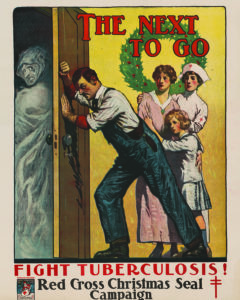

Beauty standards made room for gloom. Unlike smallpox or plague, consumption did not disfigure. Rather, its visible furnishings—slender, delicate body, pale skin setting off feverish cerise lips and cheeks, sunken eyes, overly nighttime and big, whispered breath—fabricated the consumptive seem more beautiful and romantic, not less. Dressmakers emphasized these aspects in women, forth with the modest waist, flat chest, protruding spine, and sloped shoulders associated with the disease, to create tragic beauty. Robust fashionettes used cosmetics to mimic the consumptive's pallid, feverish face up. Belladonna eyedrops caused pupils to amplify with delirious intensity. The poet Lord Byron said he wished to die of consumption, "because the ladies would say: 'Look at that poor Byron, how interesting he looks in dying.'" Byron was amidst those Romantics holding that consumption brought on a practiced death, killing slowly, sweetly, beautifully; malaria probable killed him.Consumption's prominence as a protomeme faded as the 19th century progressed. One factor was the Civil State of war's industrial-strength killing. Photographs of rotting corpses on battlefields like Gettysburg and Antietam took the fun out of morbidity and mortality. In 1882, German scientist Robert Koch identified Mycobacterium tuberculosis as the bacterium that causes tuberculosis, a discovery that earned Koch the 1905 Nobel Prize.

The revelation that a germ caused consumption non just grounded doctors and patients in medical reality but launched the age of the sanitarium at the plough of the century. (see "Mountain Medicine," below). After World War II, antibiotics caused tuberculosis to autumn out of the popular imagination in the United States, although HIV-AIDS, past compromising immune systems, engendered a resurgence. Worldwide, however, the disease remains one of the height ten causes of death, yearly killing 1.5 million. For many, consumption is yet "the helm of all those men of death."

_____

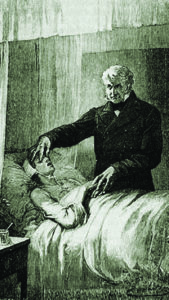

Mountain Medicine

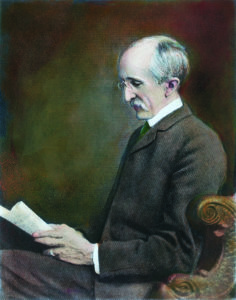

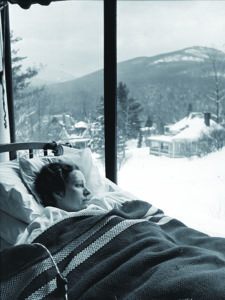

In 1885, Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, left, following a German language plan, opened the outset American sanitarium at Saranac Lake in upstate New York's Adirondack Mountains. Trudeau, himself in remission from TB after adhering to a class of residuum and a healthy diet in mountain air, wanted to replicate that treatment. As a exam, he offered poor New Yorkers lodging, board, and a regimen he oversaw. Within 15 years, Trudeau's rural rest cure experiment had grown from a few cottages to a sprawling institution. For patients able to beget them, such open-air retreats grew fashionable. The movement spread speedily as municipalities and states tried to stop consumption from infecting middle and upper-class residents by isolating poor TB patients. Tuberculosis came to be seen equally a disease of the immigrant, the poor, and the dissolute. In 1900 at that place were 34 sanitaria; by 1925 in that location were over 500, with more than one-half a million beds. Many patients plant themselves "committed" to isolated facilities imposing strict bed balance for weeks, fifty-fifty months, sometimes on open-air porches, followed by sitting outdoors in "invalid" chairs offering the optimum bending for animate. Waking and retiring, diet, even conversation were often strictly supervised. Many patients reported frustration, boredom, hostility, powerlessness, and shame at being sequestered. Arrival of streptomycin undid the sanitarium motion, whose legacy persists in sleeping porches, Adirondack chairs, mountain resorts, Thomas Mann'south Magic Mountain, and the recorded memories of sometime inmates of the "residue cure." —Mary Fuhrer

In 1885, Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau, left, following a German language plan, opened the outset American sanitarium at Saranac Lake in upstate New York's Adirondack Mountains. Trudeau, himself in remission from TB after adhering to a class of residuum and a healthy diet in mountain air, wanted to replicate that treatment. As a exam, he offered poor New Yorkers lodging, board, and a regimen he oversaw. Within 15 years, Trudeau's rural rest cure experiment had grown from a few cottages to a sprawling institution. For patients able to beget them, such open-air retreats grew fashionable. The movement spread speedily as municipalities and states tried to stop consumption from infecting middle and upper-class residents by isolating poor TB patients. Tuberculosis came to be seen equally a disease of the immigrant, the poor, and the dissolute. In 1900 at that place were 34 sanitaria; by 1925 in that location were over 500, with more than one-half a million beds. Many patients plant themselves "committed" to isolated facilities imposing strict bed balance for weeks, fifty-fifty months, sometimes on open-air porches, followed by sitting outdoors in "invalid" chairs offering the optimum bending for animate. Waking and retiring, diet, even conversation were often strictly supervised. Many patients reported frustration, boredom, hostility, powerlessness, and shame at being sequestered. Arrival of streptomycin undid the sanitarium motion, whose legacy persists in sleeping porches, Adirondack chairs, mountain resorts, Thomas Mann'south Magic Mountain, and the recorded memories of sometime inmates of the "residue cure." —Mary Fuhrer

_____

Talking TB

Tuberculosis is caused past Mycobacterium tuberculosis, a bacterium spread by contact with infected sputum. Inhaled bacilli invade soft tissue and multiply, forming nodular lesions that break down and kill tissue. These "tubercules" tin touch many organs, but most commonly attack the lungs. Onset tin can be quick, only the disease can remain latent for years, emerging under stress. Some patients defeat the illness unassisted, only without antibiotics people with active pulmonary tuberculosis commonly experience a chronic, progressive decline marked by cough, fever, chest hurting, extreme weight loss, and malaise. Every bit tubercules destroy lung tissue, hemoptysis—coughing or "spitting blood"—results. Weakened bodies eventually succumb to respiratory failure—in effect, suffocation. A characteristic profound curvature of the upper spine occurs when tuberculosis of the lungs spreads to the spine. This causes a deformity in the upper spine that makes the shoulder blades prominent and the shoulders announced curved or sloped toward the front end. Formally called Pott's Affliction, this "hump" was understood to be a feature of consumption. Until antibiotics arrived, TB dominated the popular imagination; fear of contamination was called "phthisophobia." When in 1926 Winnie the Pooh author A.A. Milne gave Christopher Robin "the wheezles and sneezles," the verse form's doctors warned "if he freezles in draughts and in breezles, the phtheezles might even ensue." TB remains the most common form of communicable diseases-related expiry in the world. —Mary Fuhrer

Source: https://www.historynet.com/the-young-and-the-beautiful/

0 Response to "On the Road Again Consumptives Traveling West"

Post a Comment